A Mosaic of Identities

Exploring genetic chimerism and its cultural significance

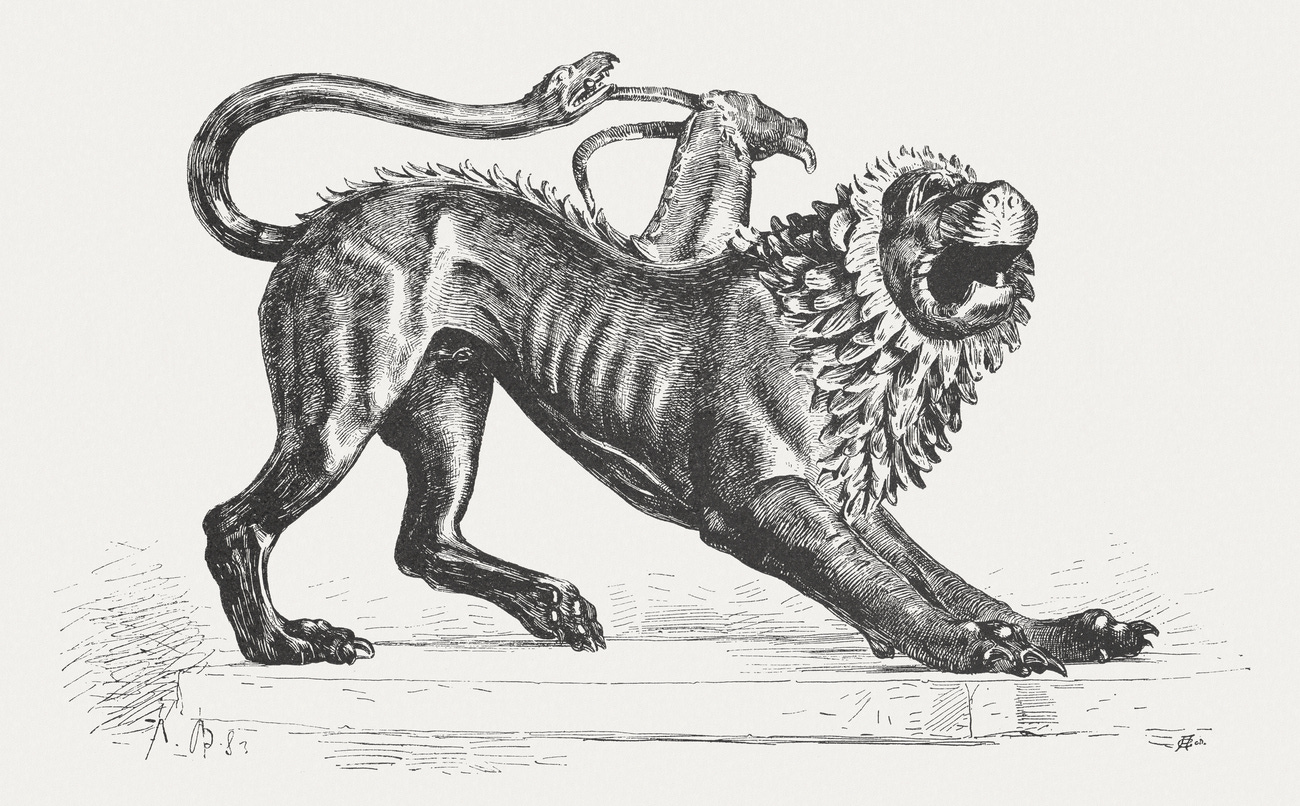

Genetic chimerism in humans and other animals has been well-documented in recent years. The term borrows from a figure in Greek mythology, the Chimera: a fire-breathing creature mashup of lion, goat, and snake body parts.

In contemporary genetics, chimerism refers to a tendency for humans to have living cells in their body with DNA that is not their own, that belongs to another human. There are two mechanisms that describe how this happens in nature.

I recently came across the concept of microchimerism from an article my mum shared from the Atlantic published in 2024. Here, I learned that a small number of cells can pass the barrier between pregnant mothers and their growing embryos. Women who have been pregnant can have cells lodged within their body that originated with their children; children have cells from their mother. This phenomenon appears to happen consistently with each pregnancy and in every organ tested.

As a result, anyone could have a small number of cells living within them from ancestors, mother and siblings, along pregnancy lines.

The research on microchimerism is still developing and its genetic benefit has yet to be uncovered definitively. It makes for some fascinating ideas for speculative fiction though!

Imagine: memories passing directly from mother to child

Imagine: pieces of each other that continue to live on following a loss

Imagine: a woman’s power that grows with each pregnancy

Imagine: honouring mothers’ bodies as collectors and distributors of genetic heritage

The second mechanism was introduced to me on a spring walk with a friend a year or two ago. She explained that macrochimerism—where a significant proportion of an individual’s DNA comes from multiple sources—happens when twin embryos fuse into a single entity in-utero. This is thought to be relatively common, affecting up to 15% of the population. It gives rise to a diverse spectrum of human experience, from heterochromia to transgender self-identification.

These two mechanisms mean that an individual’s genetics are not isolated, unique, or completely determined by the classic Punnett square from high school biology. Research suggests that we are much more complex.

Our genetic makeup may be better understood as a mosaic. Each person is a collection of pieces from an ancient and ever-evolving genetic story connecting families together, spanning generations.

My imagination lights up as I think of the weight of genetic history that each body carries and how furthering this research might impact our society in the future. Our connections to each other run deeper than previously thought; our identities less distinct. We are quite literally pieces of each other in different aspects. Perhaps one day our connectedness and our diversity will be honoured more than our independence. What might life be like then, I wonder?

If you like what you’ve read and want to hear more, consider subscribing to this publication with a free or paid subscription.